Frequently Asked Questions

For organisations, businesses and groups

Keep up to date with the coalition’s latest news, events and campaigns

Frequently Asked Questions

For organisations, businesses and groups

Keep up to date with the coalition’s latest news, events and campaigns

Humanity’s most popular industrial-scale method for catching fish is also one of the most destructive.

But we get it, you have questions. Here are our thoughts on some of the areas we get asked about a lot, but if we haven’t answered your question please contact us.

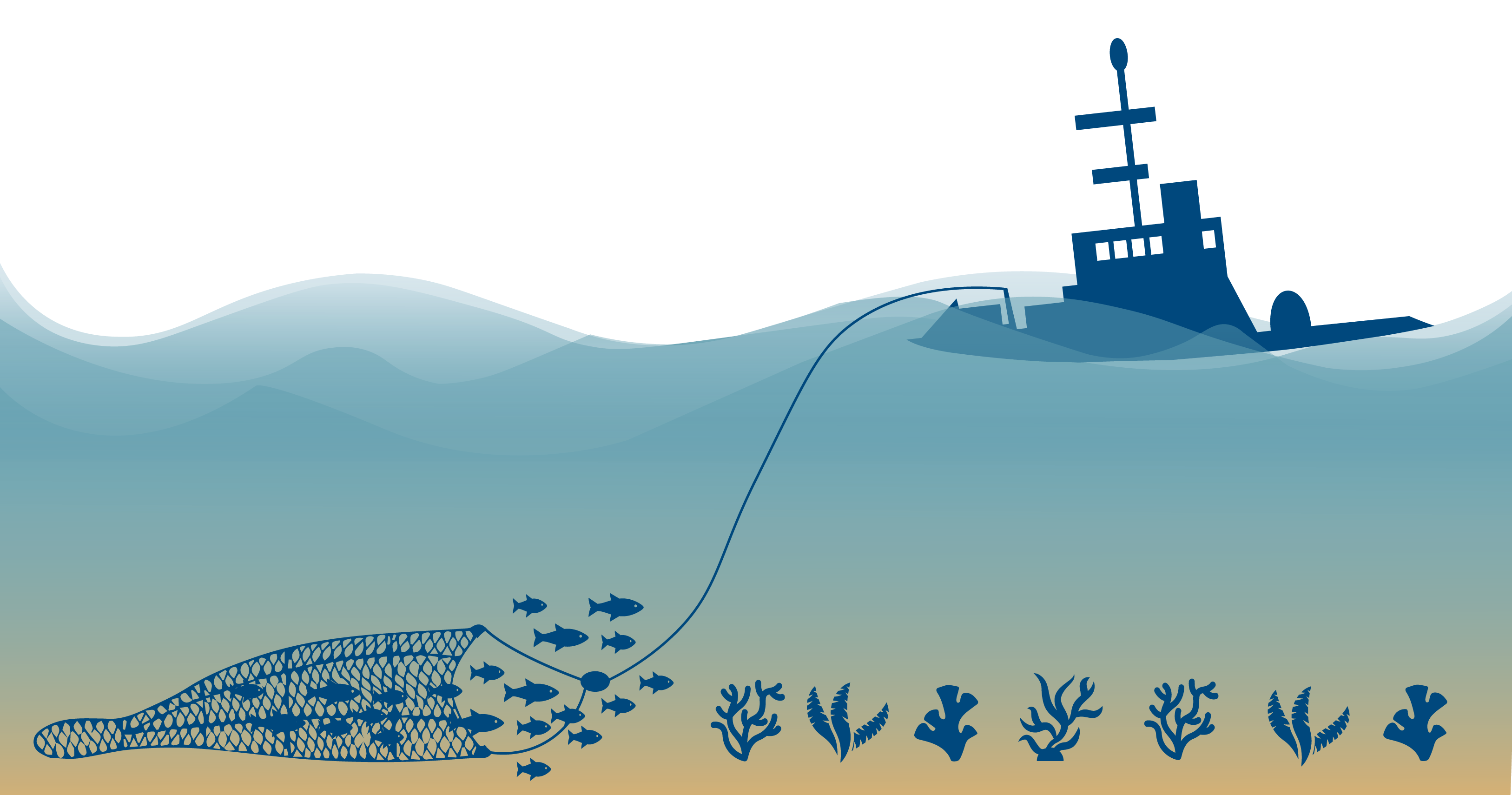

Trawling is the practice of dragging a weighted fishing net (a trawl) through the ocean in an effort to catch seafood.

Bottom trawling occurs when the net is towed along, or very near to, the seafloor. Most scientists categorise bottom trawling as either benthic or demersal. Benthic trawling occurs along the very bottom of the sea floor (the so-called benthic zone) whereas demersal trawling is slightly higher in the water column. As such, bottom trawling targets both bottom-living fish (groundfish such as flounder, plaice and halibut) as well as semi-pelagic species such as cod, squid and rockfish.

Yes, the main one is midwater trawling, which targets pelagic fish (those that live in the upper water column) like mackerel, anchovy, herring and hoki. Midwater trawlers usually fish for a single species, whereas bottom trawlers target multiple species.

Two things are needed: a boat and a net. The type of fishing boat is known as a trawler. Trawlers come in all sizes, from small open day boats of 10m in length to factory supertrawlers, which can be 150m long and able to stay at sea for months on end.

There are several types of bottom trawl net, all of which use a cone-like net with at least one closed end (the cod-end) that holds the catch. Net types differ by how their mouths are kept open. Beam trawls use a beam of wood or metal on skids (heads) that travels along the seabed. Normally used to target flatfish, beam trawls sometimes make use of tickler chains to disturb fish from the seabed. Otter trawls are the most common method. They use large, rectangular otter boards to keep the mouth of the net open, and are typically used to target demersal species such as cod and haddock.

Bottom trawling has a wide array of potentially negative environmental, socio-economic and climate impacts. Historically, much of the controversy has centred on the damage done to seabed habitats by heavy trawl nets, as well as on the large quantities of sea creatures that trawlers don’t target, but which are caught accidentally and discarded overboard. Recently, an emerging research picture is suggesting that bottom trawling may also undermine the food security of local fishers in coastal developing nations, and have out-sized climate impacts. Each of these impacts is manageable in isolation, but when you add them all together, it becomes clear that we can’t keep bottom trawling in all of the areas we currently do.

More than any other fishing method, bottom trawling destroys and damages seafloor habitats, and reduces the amount and variety of life that lives there. This changes the make up of these animal and plant communities, reducing their ability to respond and adapt to other impacts. Research has found that it takes between 1.9 and 6.4 years for seabed plants and animals to recover following trawling. Some sensitive habitats and species may never recover.

Bottom trawling is also indiscriminate. Gear modifications and better management have improved things, but lots of sea creatures are still caught accidentally – a practice known as bycatch. Over the past 65 years alone, bottom trawlers have discarded overboard more than 400 million tonnes of untargeted marine life. This includes everything from protected species and marine megafauna to commercially valuable fish also targeted by small-scale fishers. In some shrimp trawl fisheries, research suggests that levels of bycatch may be as high as 80-90%.

Around the world, over 100 million people rely on inshore subsistence and small-scale artisanal fishing for their daily food and livelihood − often using the same waters targeted by destructive trawlers. By undermining complex habitats and fish populations, bottom trawling can create conflict, out-compete local fishers and diminish fisheries that are critical to the livelihoods and food security of some of the most vulnerable people on earth. This isn’t an area that has historically been of interest to fisheries managers, researchers, policy makers, conservationists or the media, but this is starting to change. You’ll find compelling eyewitness accounts of the socio-economic damage done by trawlers in the media section of this site.

The marine sediments and habitats disturbed by trawl nets are the world’s largest carbon stores. The research in this area is still in its infancy, but each year, bottom trawling releases an estimated one billion tonnes of CO2 from the seabed, an amount that some have equated to emissions from the entire aviation sector. Whilst it’s not clear how much of that carbon will stay in the ocean and how much will end up in the sky, it’s likely to acidify our seas and further undermine the productivity and biodiversity of marine life. Then there are the emissions from the trawlers themselves, which are among the highest of any method of food production. Simply put, business-as-usual bottom trawling is incompatible with a net zero world.

Yes. The research picture on this is improving all the time. The best evidence we currently have suggests that 14% of the world’s continental shelves and slopes are trawled. This number differs markedly across regions, from 0.4 percent in southern Chile to 80 percent in the Adriatic Sea.

Bottom trawling is a special case. When you add together the damage it does to habitats, marine life, coastal communities and the planet, it’s clear that it’s in a league of its own. Bottom trawling undermines local food security and brings conflict to vulnerable coastal communities. No other method of fishing causes so much damage. No other method of fishing is as incompatible with the path to a low carbon world. For the planet, for the ocean and for the hundreds of millions of people who depend upon it to eat and to live, we need to urgently tackle bottom trawling.

Well, bottom trawling is the worst offender: it’s the most widespread human-caused disturbance to seabed habitats globally. In fact, because it pre-dates newer industries like renewable energy, in many ways, bottom trawling has fewer environmental safeguards than other parts of the blue economy. Erecting an offshore wind farm requires a lengthy and expensive planning process with comprehensive stakeholder consultations and voluminous environmental impact assessments. Such farms are not without their environmental issues, but the damage to the seabed they cause is essentially a one-time thing. We don’t repeatedly smash wind turbines into the seafloor, yet we do repeatedly bottom trawl.

Actually, compared with other industries like offshore energy, bottom trawling isn’t particularly regulated. Around the world, there’s an increasing push to ensure that organisations demonstrate not only “no net loss” but also “net positive impact” – offsetting or restoring post-impact. But bottom trawl companies have zero obligations to restore the habitat they impact.

And while there’s been welcome progress in recent years in identifying so-called vulnerable marine ecosystems to avoid, the sad fact is that identifying VMEs is prohibitively expensive for many States. Further, with many so-called protected areas allowing bottom trawling and with the high seas still a free-for-all, it’s hard to argue that bottom trawling is already highly regulated.

Finally, our world is warming, and along tropical coastlines, food security for local fishers is a growing concern. As our blue planet changes, so too must regulations governing its use.

It’s certainly true that management measures can reduce some of the most harmful impacts through seasonal or area-based closures, move-on rules, mesh size regulations, quotas, bycatch reduction efforts, and observer systems, among others.

And it’s certainly true that capacity for enforcement, governance and management differs from place to place. But that isn’t an argument against regulation. We can’t just give up on creating better policies altogether. That way lies a world that has given up the struggle against climate change and given up hope of vibrant, sustainable oceans teaming with life.

We are working with and supporting governments to improve regulation and enforcement. A number of tropical developing nations have already put in place near-shore exclusion zones for artisanal fishers, but these are often ignored by industrial operators. The sad fact is that many States don’t have the resources or the political appetite to fight back, so as long as the subsidies continue, so too will the transgressions.

It’s true that the Marine Stewardship Council has certified as sustainable a number of bottom trawl fisheries. In fact, there are more fisheries in the programme that use bottom trawls than any other gear type. However, no coastal bottom trawl fisheries in developing nations have been certified, and the MSC doesn’t consider the socio-economic and climate impacts of a fishery as part of the certification process. Sustainability, for them, is limited to environmental aspects only. But because of their cumulative impact on climate, environment and people, bottom trawl fisheries are a special case.

This is a pro-fishing campaign. It’s pro-livelihoods and pro-sustainability. We believe these things don’t have to exist in opposition with one another. We recognise that many bottom-trawl fleets are not deliberate architects of environmental damage, but the product of favourable national subsidies and loose regulation. Such subsidies constitute one of the greatest market failures the ocean has ever seen, and continue to prop up fisheries that would otherwise be financially unsustainable.

While we recognise that some of these fleets have been beneficial for coastal communities over the short term (by delivering employment on board vessels and in processing facilities, and bait to small-scale fishers), over the longer term, fishing this way simply isn’t sustainable. That’s why we want to see states redirect those harmful subsidies and take a range of bold steps to support a just transition, safeguard the rights of displaced workers, and tackle the unintended consequences of trawling restrictions.

We’re growing a broad coalition of small-scale fishers, seafood companies, conservationists, local tourism businesses, scientists, managers and fisheries policy experts that’s devoted to inclusive, holistic and lasting change. We’re pro small-scale fishing, we’re pro environment and we’re dedicated to bringing the needs of coastal communities to the fore.

Actually, bottom trawling isn’t a viable option in most places. It only persists because it’s subsidised. Without those subsidies, it wouldn’t be economically worthwhile. There are alternatives and management measures (e.g. less damaging gears) but it’s true that these will not be applicable in all contexts. Fisheries managers everywhere have common goals. They need to ensure that ecosystems and fish stocks remain healthy to deliver benefits long into the future. But they operate in vastly different environments with varied priorities, resources, and values, and it is these which will govern the best blend of measures.

That said, we are a pro-fishing coalition and we recognise that there would be significant short-term livelihood implications to an immediate global ban on bottom trawling. That’s why we’re calling for something less radical: a ban in coastal waters and in MPAs, and a frozen trawling footprint.

Bottom trawling can be hugely devastating for marine ecosystems and those who rely upon them to eat and to live.

Trawl nets as wide as a football field plough up the seabed, destroying vast amounts of marine life. Fragile habitats that provide food and shelter for a huge and varied range of sea creatures can be ripped to shreds. Many never recover.

Over the past 65 years alone, bottom trawlers have discarded overboard more than 400 million tons of untargeted marine life.

This includes everything from protected species and marine megafauna to commercially valuable fish also targeted by small-scale fishers. Had this catch been landed, it would have been worth around US$560 billion.

Over 100 million people rely on inshore subsistence and artisanal fishing for their daily food and livelihood − often the same waters targeted by destructive trawlers.

The destruction wrought by bottom trawling goes much deeper than the glaring loss of marine life. By pulverising complex habitats and undermining fish populations, bottom trawling creates conflict and diminishes fisheries that are critical to the livelihoods and food security of some of the most vulnerable people on earth.

Bottom trawling pumps out one billion tons of CO2 each year, an amount an amount that some have equated to emissions from the entire aviation sector.

The marine sediments disturbed by trawl nets are the world’s largest carbon stores. Bottom trawling releases carbon from the seabed into the water, increasing ocean acidification, and further undermining productivity and biodiversity. Plus there are the emissions from the trawlers themselves, which are among the highest of any method of food production.

We want to see bottom trawling urgently tackled by all coastal nations, with evidence of a globally reduced footprint by 2030.

Keep up to date with the coalition’s latest news, events and campaigns. By signing up to the newsletter you agree to receive emails from the Transform Bottom Trawling Coalition on issues related to coalition. Your contact information will not be shared or publicised.